Contents

Ever had your power suddenly go out for no obvious reason? Or noticed a strange burning smell from your breaker panel? These aren’t just random issues—they could be signs of a dead short or a dangerous short circuit threatening your home or facility. Worse, many people don’t understand the difference between a ground fault and a bolted fault, which makes responding correctly even harder. In this article on the Tech4Ultra Electrical website, I’ll walk you through everything you need to know to spot these electrical faults, understand what causes them, and take the right action before things get worse.

Brief Explanation of Electrical Faults

Electrical faults are abnormal conditions that disrupt the normal flow of current in an electrical system. They can be caused by insulation breakdown, equipment failure, or human error. The most common types include short circuit, ground fault, dead short, and bolted fault. Each type presents different symptoms and levels of danger, but all require immediate attention to avoid damage or hazards.

Importance of Understanding Dead Shorts for Safety and Troubleshooting

A dead short is one of the most dangerous electrical faults because it allows maximum current to flow instantly with almost zero resistance. This can lead to overheating, fire, or complete system failure in seconds. Knowing how to identify a dead short is crucial for both electricians and homeowners. It enhances safety, minimizes risk, and speeds up troubleshooting by helping you isolate and address the issue before it escalates into a costly disaster.

What is a Dead Short?

Definition and Characteristics

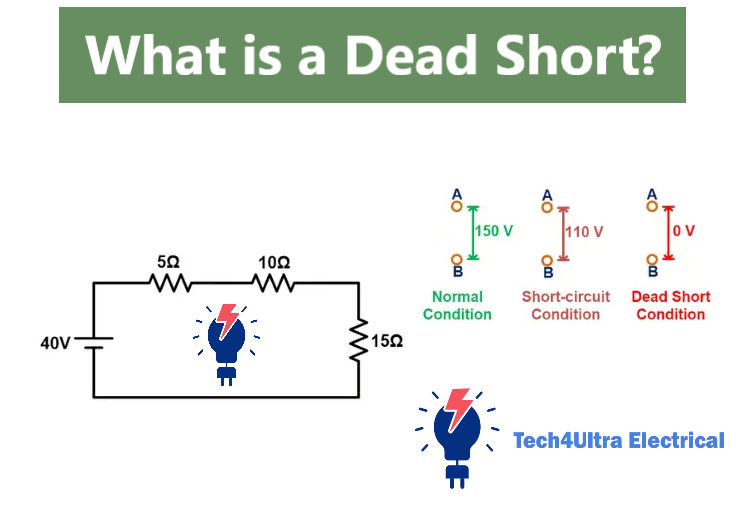

A dead short is a severe type of electrical fault that occurs when a live wire directly touches a neutral or ground wire, creating a path of zero resistance. This causes a sudden and massive surge of current that can instantly damage wires, trip breakers, or even cause fire. It’s called “dead” because the circuit effectively bypasses all resistance—killing the normal function of the system.

Electrical Theory: Zero Impedance and Excessive Current

From a technical perspective, a dead short results in what’s known as zero impedance. With no resistance to limit the flow, the electrical current spikes dramatically, often thousands of amps, depending on the circuit. This is extremely dangerous and can overheat wires within seconds. It’s a classic case of current taking the path of least resistance—with catastrophic consequences.

Difference from Other Faults

Unlike a regular short circuit, which may have some resistance due to damaged insulation or contact through a conductive object, a dead short is a direct connection with no buffer. Compared to a ground fault, which usually leaks current through unintended paths, or a bolted fault, which involves fixed metal-to-metal contact, the dead short is the most intense and destructive form.

Read Also: What Is Clamping Voltage? How It Protects Your Devices

Dead Short vs Short Circuit vs Ground Fault

Detailed Comparison Table

Understanding the differences between a dead short, short circuit, ground fault, bolted fault, arcing fault, and phase-to-ground fault is crucial for accurate diagnosis and repair. Here’s a comparison table to help you quickly identify and differentiate between these fault types:

| Fault Type | Definition | Impedance | Common Cause | Severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead Short | Direct contact between hot and neutral/ground with zero resistance | Zero | Wire damage, accidental contact | Extreme |

| Short Circuit | Low-resistance path between two conductors | Low | Insulation failure | High |

| Ground Fault | Unintended path from hot to ground | Varies | Moisture, damaged wire | Moderate to high |

| Bolted Fault | Rigid, fixed metallic connection between phases | Very low | Mechanical fault, maintenance error | Very high |

| Arcing Fault | Sparking fault due to air gap between conductors | Variable | Loose connections, wear | Moderate |

| Phase-to-Ground | Hot wire contacts grounded surface or conductor | Depends on path | Improper grounding, damaged insulation | High |

Visual Diagram Suggestion

To enhance clarity, a visual diagram showing each fault type’s current path would be highly effective here. For example, illustrate how a dead short bypasses the load entirely, while a ground fault leaks to the chassis or earth. Diagrams can be placed side by side for quick visual comparison.

Watch Also: What Is Available Fault Current and How to Calculate It

Common Causes of Dead Shorts

Damaged Insulation

One of the most frequent causes of a dead short is damaged insulation. Over time, heat, friction, or rodents can wear away the protective coating on wires. Once the conductor is exposed, it can make direct contact with neutral or ground, instantly triggering a short circuit—and if resistance is zero, a full-blown dead short.

Loose Connections

Loose wire connections inside panels, outlets, or switches can shift or vibrate over time, eventually touching where they shouldn’t. A terminal screw not properly tightened could allow a live wire to move and contact grounded metal surfaces, resulting in a dangerous ground fault or dead short.

Water Ingress

Water and electricity are a disastrous mix. Moisture entering junction boxes, panels, or cable trays can create conductive paths between hot and grounded components. This often leads to corrosion, but in severe cases, a dead short can occur almost immediately—especially in outdoor or basement setups.

Equipment Failure

Old or defective equipment, such as motors, HVAC units, or transformers, can internally fail and create a bolted fault or short circuit. If the internal breakdown results in direct conductor-to-conductor contact, the result is typically a dead short with catastrophic consequences.

Effects and Dangers of Dead Shorts

Circuit Breaker Trip

When a dead short occurs, the current surge is so intense that it immediately trips the circuit breaker. This is the first line of defense to prevent further damage. If the breaker fails or is improperly rated, the system can remain energized—making the situation far more dangerous.

Equipment Damage

Excessive current from a short circuit can destroy sensitive components in seconds. Motors may burn out, control boards can be fried, and wiring insulation may melt. A dead short leaves little time for response, making it one of the most damaging electrical faults.

Electrical Fires

The heat generated from unrestricted current flow can ignite nearby materials, leading to electrical fires. Arcing and burning insulation add to the risk. If not contained, a dead short can escalate into a full-blown fire emergency within minutes.

Human Safety Risk

Perhaps the most serious consequence of a dead short is the threat to human life. Shock hazards increase dramatically, especially if someone is near the fault or attempting a repair. Faulty ground protection or slow breaker response can result in severe injury—or worse.

Watch Also: Electrical Switchgear Protection Explained

How to Detect a Dead Short

Step-by-Step Method Using a Multimeter

One of the most reliable tools to detect a dead short is a digital multimeter. Here’s how you can do it safely:

- Power Down: First, ensure the circuit is completely de-energized. Turn off the breaker and verify there’s no voltage.

- Use Continuity Mode: Set the multimeter to continuity mode. Place one probe on the hot wire and the other on the neutral or ground. If you hear a beep, that indicates a path—possibly a short circuit.

- Switch to Resistance Mode: Still with the power off, switch to ohms mode. A reading of near 0 ohms between hot and neutral or ground suggests a dead short.

- Trace the Fault: Isolate different parts of the circuit (e.g., by removing outlets or switches) and retest to narrow down the exact location of the fault.

Use of Insulation Resistance Tester and Megger

For deeper diagnosis, especially in industrial or complex wiring systems, an insulation resistance tester (commonly called a megger) is ideal. This tool applies a high DC voltage and measures leakage current:

- High Megohm Readings: Indicate good insulation.

- Low Megohm or Zero: Suggest a dead short or degraded insulation.

Always follow safety protocols when using high-voltage testers, and ensure all equipment is grounded properly.

Practical Tips for Electricians

- Label all wires before disconnecting.

- Inspect visually before testing—melted insulation or burnt terminals are red flags.

- Use a clamp meter to detect current draw if the breaker keeps tripping under load.

- Log your test results—consistency helps spot hidden faults.

How to Fix and Prevent a Dead Short

Safe Power-Off Procedures

Before attempting any repair on a suspected dead short, always shut off power at the main breaker panel. Verify with a voltage tester that the circuit is completely de-energized. Never rely solely on the breaker label—test every wire to confirm it’s dead.

Component Replacement

Once isolated, inspect switches, outlets, and junction boxes for burned or melted parts. Any damaged components must be replaced, not repaired. If a short circuit occurred inside an appliance, it’s safer to replace the appliance or have it professionally serviced.

Insulation Checks

Use an insulation resistance tester or megger to check wiring integrity. If the reading is low, the wire’s insulation may be compromised. Replace any cable with cracked, brittle, or melted insulation to eliminate risk of another dead short or ground fault.

Installation of GFCI and Proper Grounding

Install GFCI outlets in kitchens, bathrooms, and outdoor areas to protect against ground faults. Also, ensure all outlets and fixtures are properly grounded. Grounding helps redirect excess current safely, reducing the chance of shock or fire.

Use of Overcurrent Protection

To prevent future dead shorts, make sure every circuit is protected by a correctly rated circuit breaker or fuse. Consider arc fault circuit interrupters (AFCIs) for added safety. These devices detect abnormal current patterns and shut down power before serious damage occurs.

Dead Short Scenarios: Real-World Examples

Residential Case

A homeowner notices the lights flickering before the entire circuit shuts down. An electrician finds a dead short behind a wall outlet—caused by a nail piercing a wire during a renovation. The breaker tripped instantly, but the insulation was already burned.

Prevention: Always use wire-mapping tools before drilling and ensure all wiring is properly routed away from high-risk areas.

Industrial Case

In a manufacturing plant, a bolted fault occurs when a motor terminal contacts the grounded chassis. The resulting dead short damages the motor, disrupts production, and trips the main breaker.

Prevention: Use proper torque settings, secure all terminals, and perform regular thermal inspections with infrared cameras.

Automotive Case

A car owner reports the fuse blowing repeatedly when starting the vehicle. A short circuit is found in the starter wire, where a frayed section touched the engine block—creating a dangerous dead short.

Prevention: Routinely inspect wiring harnesses and secure all cables away from vibrating or sharp components.

Watch Also: Armature in Electric Motors and Generators: Structure, Function, and Key Differences

Testing and Troubleshooting Tools

Multimeter

A digital multimeter is the first tool any electrician should reach for when diagnosing a dead short. It can test continuity, resistance, and voltage. Use continuity mode to detect direct connections between hot and ground or neutral, which often indicates a short circuit.

Megger (Insulation Resistance Tester)

A megger applies high-voltage DC to test insulation between conductors. It’s especially useful for identifying deteriorated insulation in large industrial systems. Low resistance readings can signal the early stages of a ground fault or a hidden dead short.

Thermal Camera

A thermal imaging camera can detect heat signatures from overloaded wires or failing components. It’s ideal for spotting potential bolted faults or overheating before they become full-blown dead shorts. This tool is invaluable in both residential and commercial inspections.

When to Call a Licensed Electrician

If you experience repeated breaker trips, see scorch marks, or hear buzzing from panels, it’s time to call a pro. Diagnosing complex dead short scenarios without proper training can be dangerous. A licensed electrician has the expertise and equipment to handle the issue safely.

Conclusion

To recap, a dead short is a severe form of short circuit with zero resistance between conductors, resulting in an immediate and dangerous current surge. It differs from a ground fault, which involves current leakage, and a bolted fault, which is a fixed metal contact fault. Detection typically involves using a multimeter, insulation resistance tester, or thermal camera. Fixing the issue requires isolating power, replacing damaged components, and checking insulation integrity.

Most importantly, never compromise on safety. Always turn off power before troubleshooting, and don’t hesitate to call a licensed electrician for complex or persistent issues. Perform regular inspections of panels, wiring, and outlets, especially in older buildings or high-moisture areas. Install GFCI outlets and ensure proper grounding across your electrical system. Preventing a dead short isn’t just about saving equipment—it’s about protecting lives.

FAQs

What is the difference between a ground fault and a dead short?

A ground fault occurs when electrical current unintentionally flows from a hot wire to the ground, usually through a compromised path such as moisture or damaged insulation. A dead short, on the other hand, is a direct connection between a hot and neutral or ground wire, with zero resistance. This creates a massive surge in current, making dead shorts far more dangerous and destructive than typical ground faults.

What are the four types of electrical faults?

The four main types of electrical faults are:

- Dead Short: Direct connection with zero impedance.

- Ground Fault: Current leaks to ground unintentionally.

- Bolted Fault: Fixed metal-to-metal connection causing a low-impedance fault.

- Arcing Fault: Electrical discharge through air due to gaps or damaged insulation.

These faults vary in intensity and cause, but all require immediate attention to maintain electrical safety.

What is a dead short circuit?

A dead short circuit is the most extreme form of a short circuit, where a live wire touches a neutral or ground directly, bypassing all resistance. This results in an instantaneous spike in current, which can lead to equipment damage, fires, or serious electrical hazards if not interrupted by a breaker or fuse.

What is the difference between a short circuit and a grounded circuit?

A short circuit refers to any unintended low-resistance path between two conductors, typically hot to neutral or hot to ground. A grounded circuit, by contrast, refers to a properly configured system where all conductive parts are safely connected to earth ground to protect against electrical faults. Confusing the two can lead to unsafe diagnostics and repairs.

What is a bolted short circuit?

A bolted short circuit is a type of electrical fault where two or more conductors make direct metal-to-metal contact, with no arc or resistance between them. This fault typically happens when hardware like bolts or busbars connect live wires unintentionally, causing an immediate and massive surge of current. Unlike arcing faults, bolted faults don’t produce visible sparks—but they can severely damage equipment and require strong overcurrent protection to isolate quickly.

What are the three types of circuit faults?

The three primary types of circuit faults are:

- Short Circuit: A low-resistance connection between two points in a circuit, often causing high current flow.

- Ground Fault: Occurs when current unintentionally flows from a hot wire to ground.

- Open Circuit: Happens when the normal flow of electricity is interrupted, often due to a broken wire or disconnected terminal.

Each type affects the circuit differently and may require unique detection and repair methods to ensure safety and functionality.

3 thoughts on “System of Wiring: Types, Uses, and Tips”